My name is Maya. I am 9 years old. My parents are named Muhammed and Fatima. We’re from the city of Herat in Afghanistan. I departed my home while still in my mother’s stomach. I don’t recall any one of my neighbors in Herat. We headed to Iran from Afghanistan; I was born in Iran. From there, we went to Greece. Then we departed to Bulgaria. We lived for around for years in the Principovac refugee camp in Šid, Serbia, after that. That’s where I learned to speak your language, never once forgetting mine. I felt fine back in Serbia. I really feel fine, however, over here: in Salakovac, Bosnia. I wish for our border “game” to succeed and for us to reach Switzerland. I want to be a doctor and help people.

These are the words of a nine-year old girl which began her search for a better life in her mother’s womb. She is a resident of Mostar and knows our language fluently, aiding everyone in the Salakovac refugee camp as an interpreter. My friend Milan, who wrote the story down, promised to put it into a book. And he did.

I could not believe it the first time I had heard it. I could only recall my own son Vedran being of the same age in 1992, when I’d sent him with his mother and sister with the last humanitarian convoys out of Mostar and into places unknown. He ventured outside his birthplace at age nine. She’s been traversing to her destination of fortune for nine years.

I listened to a man’s story. He spoke as if he was talking of someone else’s journey, but also of his own pain holding him hostage. He said:

On my eighth birthday I was woken up by a loud noise – someone banged on the front door. Soldiers entered, roughly dragging along to the center of the village every single adult male. They also took my father and older brother. I hid and watched from afar. An enormous hole had been dug in the middle – deep as a swimming pool. They gathered them on the edges and asked them questions which they couldn’t answer. Then they were forced down the hole and buried alive with bulldozers. I lost my father, brother and relatives. This is why I began this journey: I do not want my children to lose their own father like that, nor do I wish for them to perish in a hole just like they did.

During the Bosnian War, I had witnessed many crimes occur. This painful testimony, however, bestowed anxiety upon me. We were all silent. A vacuum of noise was felt. Then, a woman’s soft voice spoke:

I am 36. My father gave my hand to my husband when I was 16. My husband is 17 years older than me. The first time I’d seen him was at our wedding. Such are our ways. The only thing I can recall from my childhood home is a bag always ready to be taken in case of an emergency. We’d always move and run from danger. Even my father remembers the bag he’d take with him in case of emergency. They were on their feet as well. The bag became our ensign. You know, the war had been affecting us for over 75 years now. We barely managed to unpack it during that time. This is why we went on this journey: for our children to be the ones to finally open it and put things where they belong.

These are only a handful of testimonies I’d listened to during the workshop sessions my coworkers and I had led with migrants from the Salakovac refugee camp, sponsored by the great international Project IMPACT as represented by the Local Democracy Agency in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina; the Mostar Youth Theater was the LDA’s main partner during the course.

I’ve created many workshops. I worked with many people during the sessions: various victims of crimes and abuse, soldiers who did horrid things, children, retirees and our war refugees being among them. This, however, was different.

I could only simultaneously listen to these testimonies, as well as media reports on:

- How the migrant question is not a humanitarian crisis but rather a “question of security”

- How they are “occupying” our country and how they “should be forced back to where they came from”

- How they’re all “runaway fighters hiding over here, criminals and scum”

- How they’re “changing” Bosnian and Herzegovinian demographics and are supposedly occupying us

Such reports go on spinning in circles on various media outlets. Meanwhile, I listened to painful stories of families and children wishing for playtime.

We established mutual trust. However, I fear that all of us, including the workshop organizers, the migrants and every youthful Mostar native wishing to aid them, are all, in a way, not relaxed enough and, if I may say, too cautious of one another, as if something would go awry should we take a wrong turn.

We would rarely communicate through spoken language. They spoke in languages for which we didn’t have any interpreters. We had to keep going, though. Eventually, we found some native instruments which some of them could play, surprising them. They broke into song. We joined them in this truly emotive and cathartic experience. With music came dance, and we learned both the songs and dances – in joy. Additional trust was made. They wanted to learn a traditional Bosnian song. We presented them a sevdalinka. This is where everyone’s positive aspects came to light. People were smiling, wishing to take selfies with us. The sevdalinka was key in pushing out all the sadness and pain of the stories told.

Then we made masks out of their faces, pouring a gypsum cast over their heads – children, men and women in that very order. All of them were overjoyed with them, wishing to bring them along. Staring into them, they told us of their botherations, paths, fears, hopes and lives. Noting down everything on the tapes recording their speeches, with every replay we were more and more uncertain and unsure of what was actually going on inside the tales.

This is when we heard of the phrase “game”. To them, it’s the act of illegally crossing borders to reach a final destination.

It’s more than a regular game – one of life and death, that is, as per our notes. Each of the 15 workshops in which we’d participated left us in awe and silence. It brought all of us closer, and we got to known their culture, traditions and botherations; they also sought the same from us, in a new, unprejudiced light.

What we offered them, and vice versa, was an honest show of love and understanding. These 15 workshop sessions can best be summed up by the words of a participant, the very one who watched his father being buried alive:

When we finally reach our end and settle down, we won’t be returning to our birthplace first, but Bosnia, where you are. You gave us hope and faith in humanity once more. Great men live here. Thank you all. We’ll see you next time.

The way he said it being honest and heartfelt, and with others nodding their heads and applauding, brought tears to everyone’s eyes.

Once we’d gathered all the information needed, we began working on a theatrical production. The only thing we were certain of regarding it was the name, “GAME”, with it needing to be raw and emotive, just as the workshop sessions were. We only sought after our scenic presentation of the events. After it came the folk music and dances, especially a Kurdish lullaby with insightful lyrics which even opened our senses.

It went like this:

Lay down,

No one lives forever.

Neither do I.

Take care.

Lay down, o sweet child,

Be good to life.

Stand up,

Look for yourself, see where you are,

Ask what you can do.

Lay in eternal happiness.

Please,

Bother not for imperfections.

As I sometimes wish to breathe one last time,

I take a step

And ask myself where I am.

The workshop and the play made me quit watching domestic reports on migrants. None of them tell of people we’ve met, either because they’ve never met them or they didn’t want to see them in the first place. It doesn’t take much for people to know and befriend each other. It truly is easier after that. This is why we believe “GAME”, the play, will reach people’s hearts and make them listen to the stories of the disenfranchised. Their “game” will be heard once it happens, and great men and women from Bosnia and Herzegovina will be spoken of around the globe.

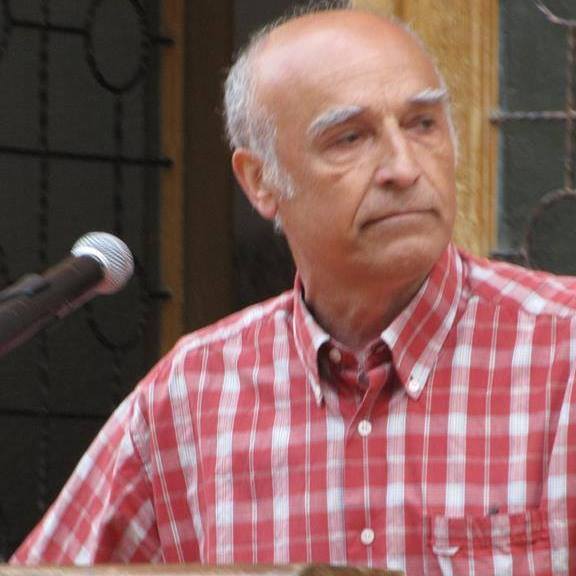

Text written by: Sead Djulic